Her Cup of Coffee

Her (most expensive) Cup of Coffee

15/09/2025

"Who wants an orange?" came a voice from the top bunk in our room, which had four bunk beds.

(Year: 1972. Location: the Beskydy Mountains, during a student ski training camp.)

"Me,

me!" I shouted from another top bunk, about three meters away from the source

of the voice.

Before I knew it, the orange landed right in my eyeball.

It had been thrown with the grace of a hand grenade – and left me with a lovely purple shiner that stayed with me long after we returned home.

And

that's exactly how I met my future best friend, Mary.

We quite literally hit it off – eye to eye, both literally and

figuratively – and within days, everyone around us knew us by our joint

nickname: HURRICANE MARY JANE.

We survived plenty of adventures together.

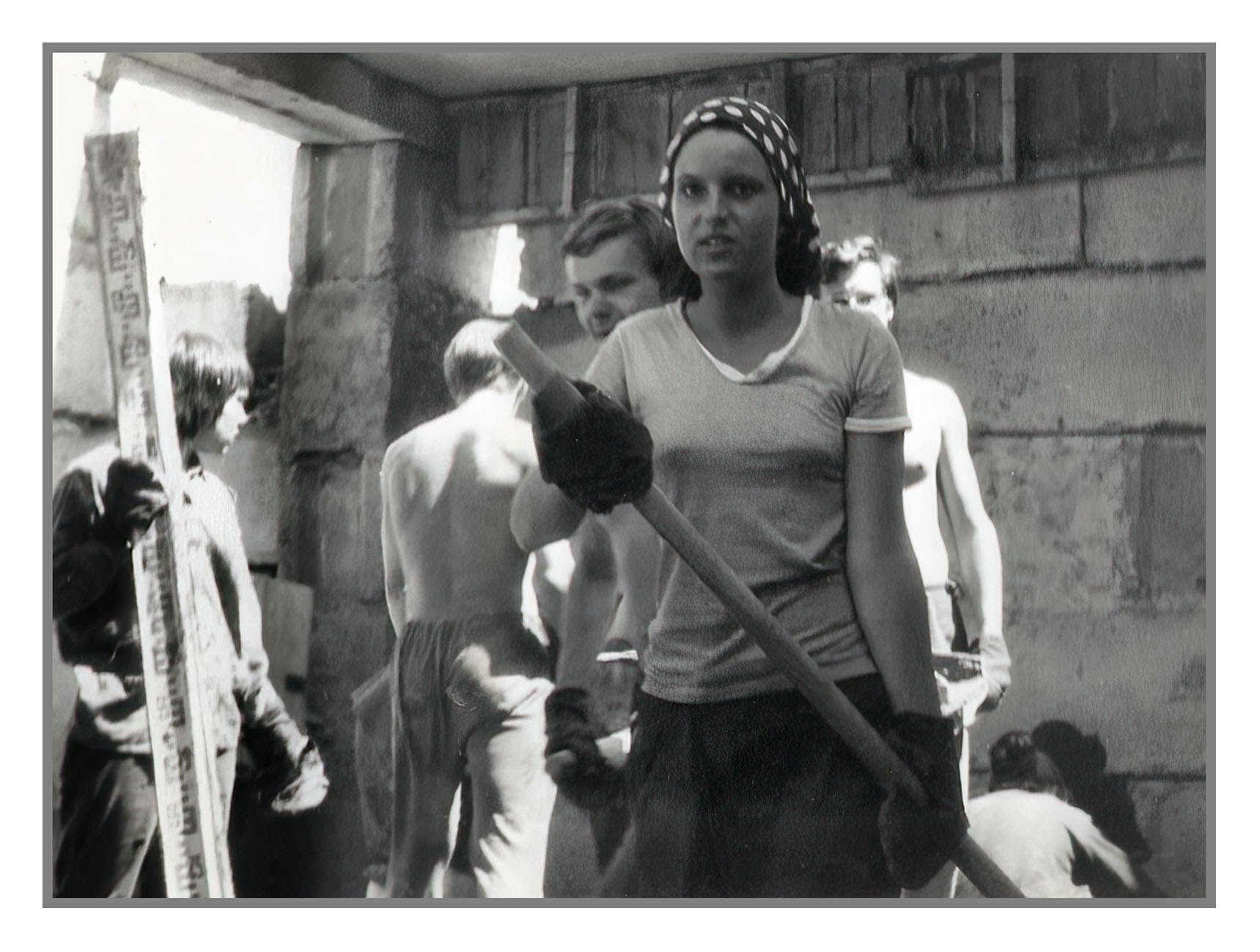

One of

the biggest was a two-month stay in the Caucasus, Soviet Union, in 1974 — part of a

mandatory internship tied to our computer science studies. We went as student

volunteers, helping build a school.

(Meanwhile, the students of the civil engineering Faculty were probably tinkering with mainframe

computers in some basement in Siberia.)

It was

the kind of experience that really tests a friendship:

Twelve hours a day with a shovel in hand, a strict ration of calories

(vodka calories not counted), and instead of showers, the obligatory evening lineup of

young communists — the so-called "lineyka" (линейка).

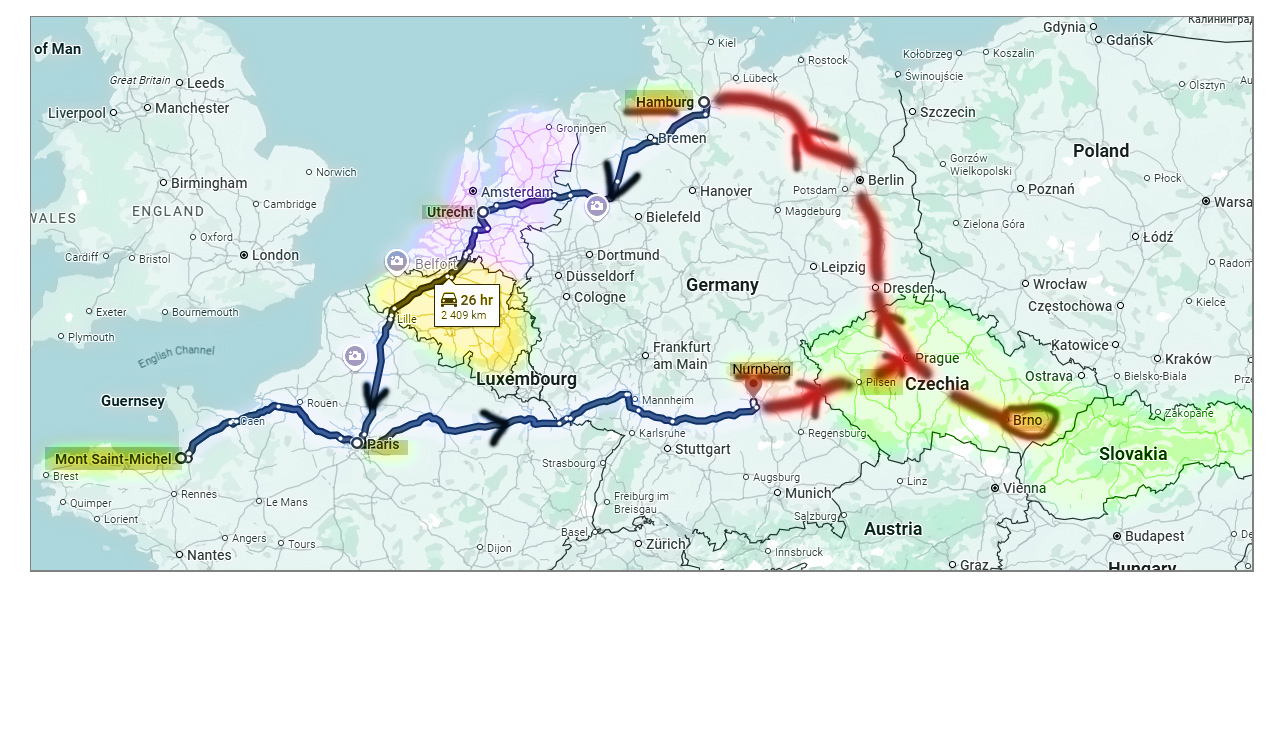

After graduation, we planned our next big trip together — this time to Western Europe.

During my student years, I worked as an English and French interpreter at the Brno Trade Fair. Besides earning some precious West German marks, we also made friends with colleagues from the West — connections that later became our "safe havens" during the dream trip we were about to take.

The

plan was simple:

Take the train to Hamburg, then hitchhike between friends and

acquaintances through West Germany, the Netherlands, and France. We'd return by train from Nuremberg, through Prague and back to Brno.

Thankfully, we were able to buy our train tickets in Czechoslovak crowns. And miraculously — the bank granted us an official currency exchange permit,

which meant we also got permission to travel abroad. At that time, this was nothing short of a miracle. Almost like winning

the lottery.

The whole journey turned into a wild adventure — full of chance encounters, improvisation, and the sheer euphoria of tasting freedom beyond the Iron Curtain.

But in this story, I want to focus on something else entirely: The culinary side of the whole trip.

The

journey began on September 23, 1978, at the Brno train station.

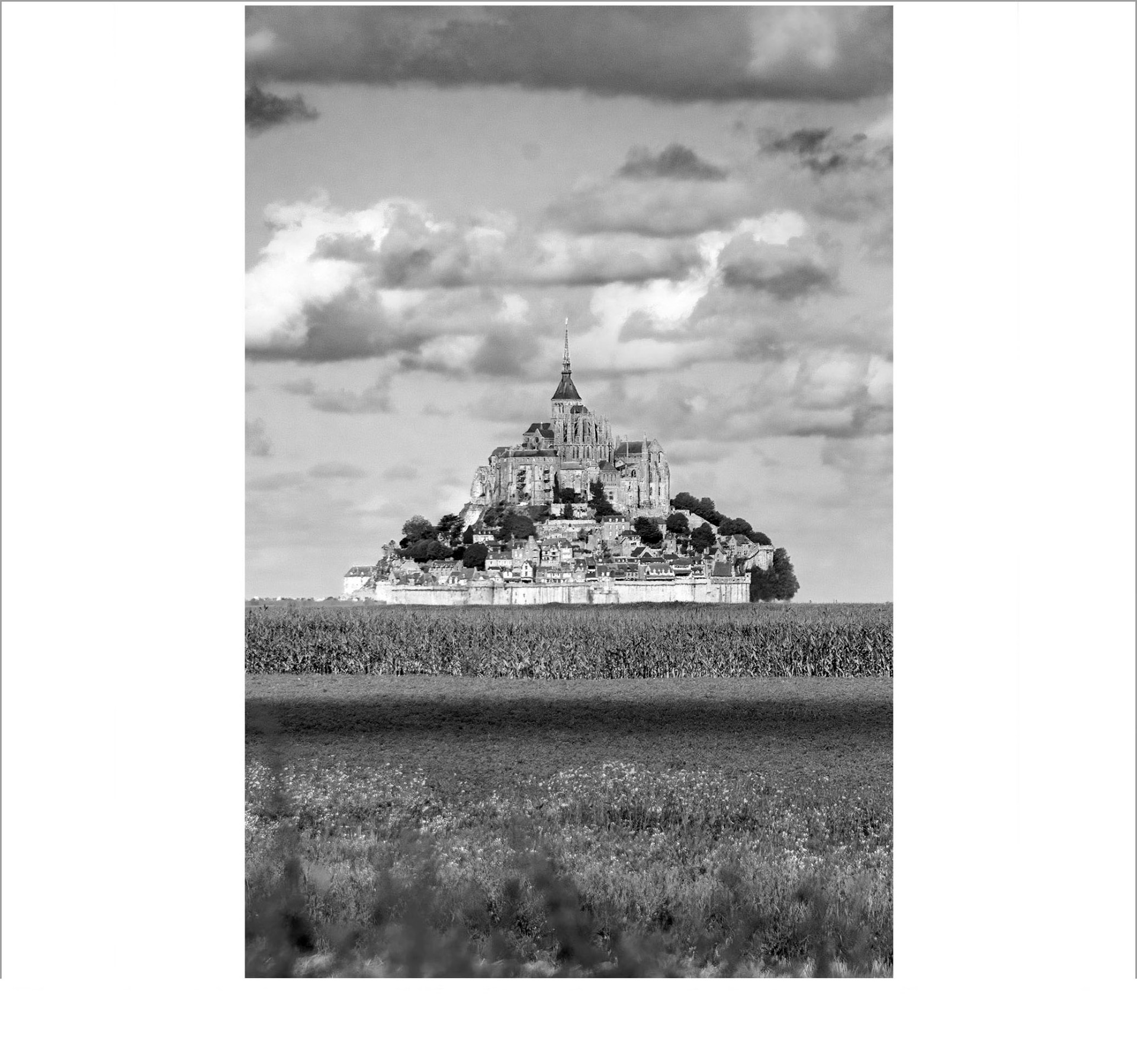

Nothing went according to plan. And yet — one week later, we made it to Paris.

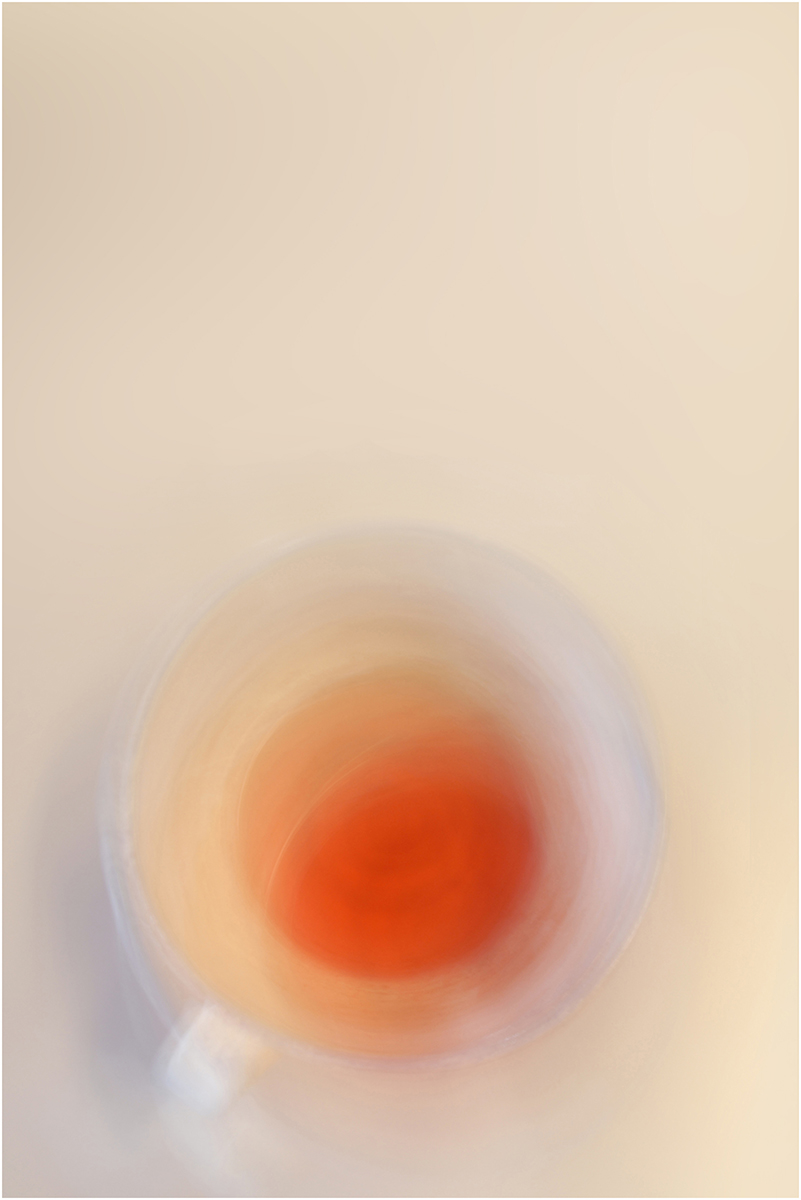

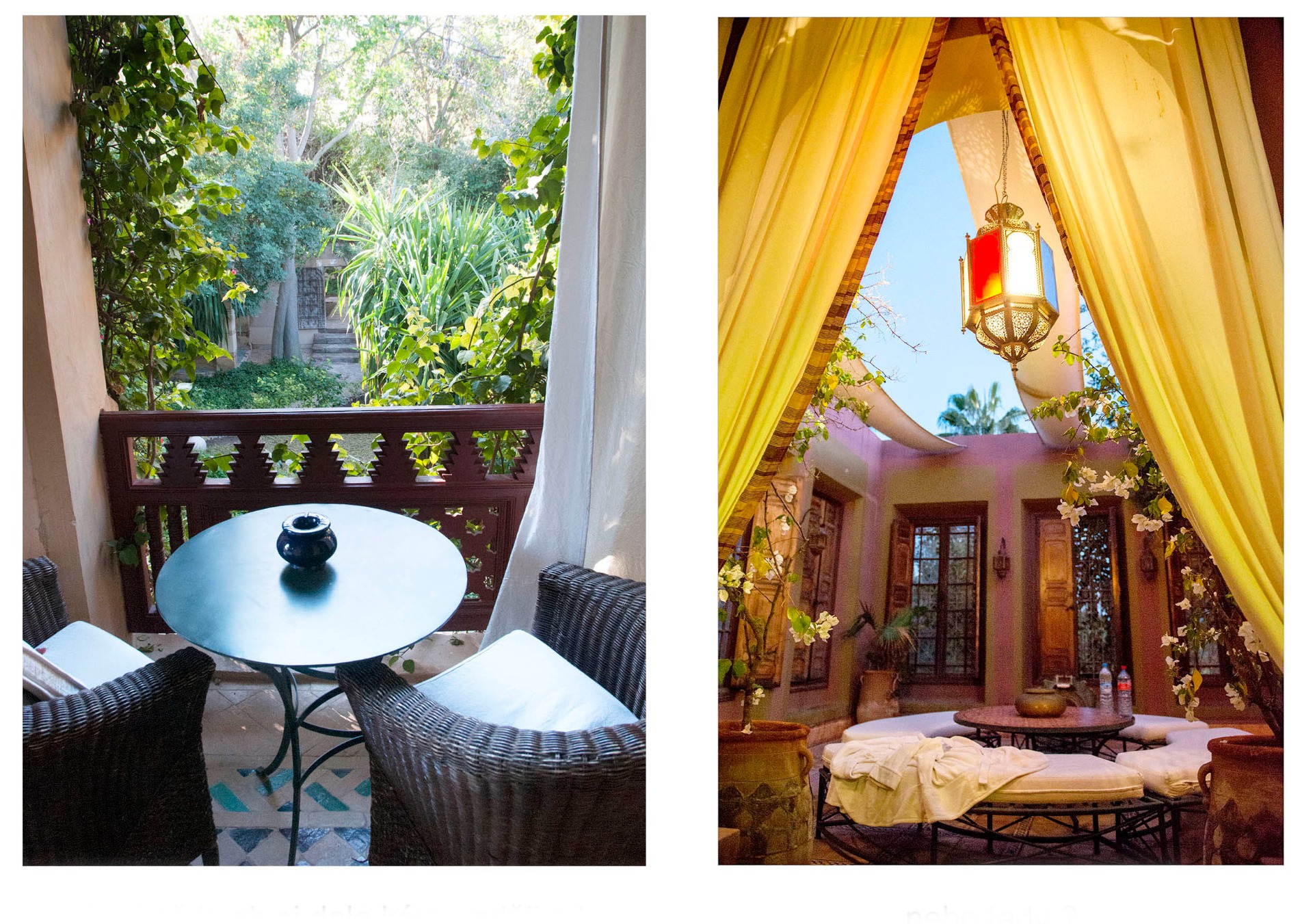

Mary had a well-known weakness for a good cup of coffee. And she was willing to sacrifice a lot for it.

"I need coffee," she declared, and confidently sat down at one of those cafés on the Champs Élysées where the waiter wears a bow tie and smiles at you, even though he knows he's serving the most expensive espresso in central Paris.

We sat outside, al fresco, with a luxury porcelain cup of hot, rich

coffee in hand — and we let the world swirl around us.

We drank it slowly. Not because it was expensive, but because we were soaking

in the moment, the role we were playing. No

maps, no backpacks. Just us and Paris, quietly watching us as we watched it back.

That

moment — that cup of coffee — became Mary's personal highlight of the

entire trip.

She would later often remind me how generously she had treated herself that

day.

And she was right — it was a splurge. By our calculations, it cost about 15 times more than a student lunch at our cafeteria (which, at the time, was just 2.80 Kčs).

October 13, 1978

Before we knew it, we were already sitting on an express train: Nuremberg –

Plzeň – Prague.

Our adventure was over — or at least, that's what we thought. Paris was once again a distant dream, and all that remained was a sweet

memory... and in Mary's case, a lingering craving for coffee.

The train made a brief stop in Plzeň. Since Paris, Mary hadn't had a single decent cup of coffee. She was getting desperate. We still had a few Czechoslovak crowns left, so the choice was clear: Mary had to run and get a "turek" (classic Czech-style coffee, grounds and all).

She glanced around, spotted a refreshment kiosk — and was

gone.

As the more experienced traveler, I shouted after her,

"What do I do if the train leaves without you? Should I pull the emergency brake?"

Mary, already outside on the platform, turned and called back with complete certainty:

"Of course! Obviously pull the brake!"

"Okay. Will do."

Moments

later, the train started moving. I looked around — no Mary.

I leaned out the window and spotted her on the platform, a paper cup of

coffee in hand, looking totally confused as the train pulled away.

Without

thinking, I acted. I pulled the emergency brake.

(Not just because she told me to — but also because the thought of having to

lug her backpack through the Prague–Brno transfer on my own? No thanks.)

We were

already past the station. The train jerked to a halt.

People jolted in their seats, confused voices filled the carriage, footsteps

rushed by, and the loud screech of metal echoed around.

I leaned far out the window, waved both arms, and shouted as loudly as I could:

"It was me! I was the one who pulled the emergency brake!"

I actually had experience from childhood — I'd been trained for this moment.

See, my mother once accidentally stopped an express train

from Brno to Prague while we were rushing to catch a flight at the Prague Airport.

In the train bathroom, she mistook the emergency brake for the toilet

flush.

She had no idea what she'd done, and even went to complain to the conductor:

"That flush handle is weird — it jerks painfully, it's

rusty, and it left a bruise on my hand!

Also, when is the train finally going to move again? We don't want to miss our

flight to Kabul!"

What she didn't know was that the train can't move again until the conductor identifies the person who pulled the emergency brake and investigates why.

Eventually, it became clear that the culprit was indeed… my

mother.

Only then could the train resume its journey. She had to pay a fine, and the

train was delayed by 30 minutes.

So yes — I knew that a fast confession is key.

This time, we just needed to catch a connection to Brno in Prague.

Mary, meanwhile, had jumped onto the train, coffee

cup in hand, half of it spilled, panting and red-faced.

But immediately we were surrounded by angry passengers, accusing us of delaying

their journey. One man even called Mary "the brake on socialist progress."

The train started moving again. And just like that — we were famous. People from other compartments came to see us, like we were part of a traveling circus.

Then came the question of the fine. Everyone insisted that whoever pulled the brake should pay. I defended myself:

"I was following orders! She told me to do it — she should pay."

In the end, the coffee Mary had chased so desperately in Plzeň ended up costing twice as much as the fancy espresso on the Champs Élysées.

She was fined 80 crowns for delaying an international express train by nine minutes. ( monthly salary of a fresh university graduate was back then 1800 crowns/month)

And so it happened that her most expensive cup of coffee wasn't served in fine porcelain on a glamorous Parisian boulevard — but in a paper cup, from a grimy kiosk at the Plzeň train station.